We remain fully operational. Our teams are working around the clock to ensure your deliveries continue safely.

Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

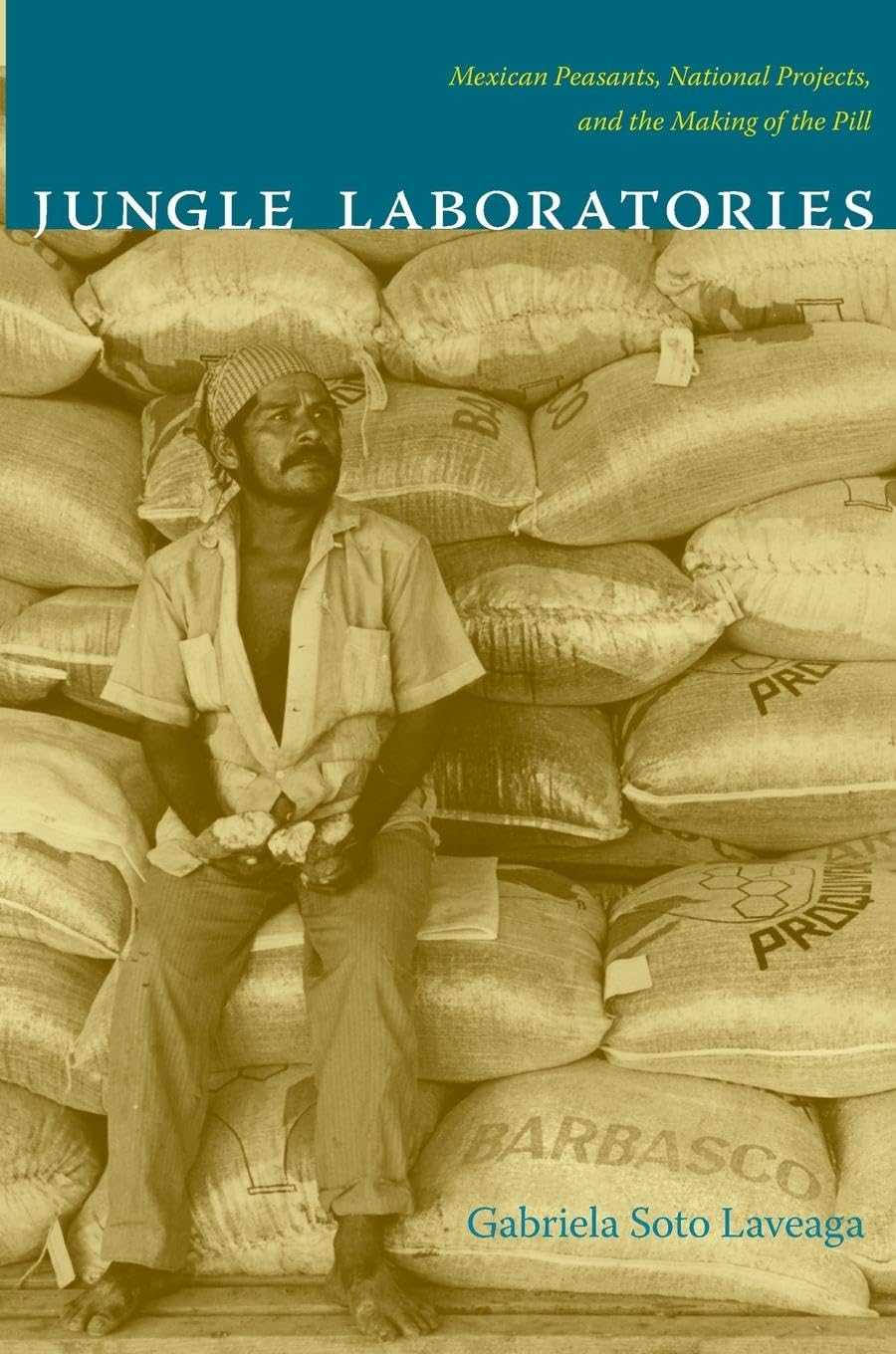

Jungle Laboratories: Mexican Peasants, National Projects, and the Making of the Pill [Soto Laveaga, Gabriela] on desertcart.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. Jungle Laboratories: Mexican Peasants, National Projects, and the Making of the Pill Review: A masterful work by an established scholar - Professor Soto-Laveaga successfully marries studies that, at first glance, appear to have little to do with each other. Yet, she convinces us that the means by which Mexican peasants hunted, processed, and sold tubers was not only scientific, but integral to the development of economically viable synthetic hormones. She raises important questions. Who produces knowledge? Where does science come from? How do human beings experience science differently? Further, she does all of this within a compelling global history of a commodity. Not to mention that I got a crash course in the history of this region. Sure, there are some portions that are stronger than others and minor imperfections here and there, but overall this is a must read for those interested in science, medicine, and globalization. Review: The story of hormones from Mexican yams. - “Jungle Laboratories: Mexican Peasants, National Projects, and the Making of the Pill,” by Gabriel Soto Laveaga, Duke University Press, Durham, NC, 2009. This 332-page paperback tells the story of the Mexican yams that made possible the birth control pill. In 1942, chemist Russell Marker of Penn State University found a wild yam in Mexico with a natural steroid suitable for conversion to hormones. This discovery is the basis of Syntex. Steroids are a family of chemicals with four condensed rings. Best known is cholesterol, but the family includes both male and female sex hormones as well as cortisone. Traditionally they were extracted from butchered animals but processing made them expensive. Yams changed all of that making steroidal hormones inexpensive and readily available. The book focuses on the peasants (campesinos) who collected the yams in a poor region of Southern Mexico. The yams were a source of income although middlemen often got most of the proceeds. The peasants were told the yams were used to make Fab detergent. Skilled pickers learned which were most valuable. Cultivation of the yams was attempted in Guatemala and Puerto Rico but yields were unsatisfactory. Russell Marker developed processes for the yams. He helped found Syntex in Mexico in 1944. He left when partners didn’t share profits. Carl Djerassi was a key player in the development of the pill at Syntex in California. Margaret Sanger was a major factor in the quest for the birth control pill. She was assisted by Gregory Pincus who did fundamental research. At the height of the barbasco trade ten tons of wild yams were removed from Oaxaca, Veracruz, Tabasco, and Chiapas states in Mexico per week by more than 100,000 pickers. Collectors received 10 to 60 Mexican centavos (less than a nickel) per kilogram. Campesinos wrote the President requesting roads, school houses, and electricity. Middlemen were central figures. They loaned tools to pickers in return for yams. The yams grew in dense jungle. Barbasco harvested in Veracruz was fermented, dried, bundled and shipped to Syntex in Mexico City. Other regions supplied German, Dutch and American companies. In 1941, cortisone proved effective in treating rheumatoid arthritis. Daily injections gave near complete remission. A mad scramble followed–almost as big as penicillin–to find a better source. In 1951, methods were developed to make cortisone from barbasco. In Mexico, Syntex got there first, but Upjohn soon found a fermentation process that converted progesterone from Syntex. In 1951, Upjohn ordered 10 tons of progesterone from Syntex. Global drug companies soon had subsidiaries in Mexico. Marker was born in Hagerstown, MD and studied chemistry at University of Maryland. He began the study of steroids at Rockefeller Institute but left in 1934 over a dispute on his search for plant sources of natural steroids. He moved to Penn State University where he worked on steroids under a grant from Park, Davis & Company. He published 147 papers on sterols and 75 patents (assigned to Park, Davis) between 1935 and 1943. The study of sex hormones began in the 1920s. In the 1930s, European pharmaceutical companies ran a cartel based on patents and cross-licensing agreements. Sex hormones were synthesized from cholesterol from the spinal cords of cattle or isolated from the urine of mammals, especially pregnant mares. Hormones for treatment of menopause was an early use. In 1942, Marker brought the first yams to Park, Davis, but they declined participation. He then approached other companies, but without success. He returned to Mexico on his own and took yam extract back to the US where a friend let him use his lab for one third of the progesterone produced. They made 3 kg valued at $240K. Next he partnered with Laboratorios Hormona SA in Mexico City to found Syntex in 1944. He had no capital but offered know how in return for 40% of profits. The price of progesterone fell to less then $1/gram. He left the company less than one year later. He did not reveal his process. Next he founded another company, Botanica-Mex SA. It was one of six companies producing hormones in Mexico. Marker left the company in 1949. He left chemistry and took up training silversmiths. To replace Marker, Syntex hired George Rosenkranz, a Hungarian born chemist who had settled in Cuba. To develop the chemical industry in Mexico he started a PhD program at National Autonomous University (UNAM) and lobbied for financial support at Instituto de Quimica. Instituto continues as the flagship of research in Mexico. A key player at Syntex was Luis Ernesto Miramontes. He made the first sample of norethindrone, which proved suitable for oral contraceptives. He attended UNAM. Carl Djerassi hired him at Syntex. Mexican peasants had known barbasco for its medicinal properties. If slices were thrown into water fish would come to the surface gasping for air. Healers used it as an abortifacient. A glass of tea was sufficient but could kill the mother as well as the fetus. Until World War II, European companies had dominated the pharmaceutical business. That changed after the war when patents from German companies–especially Schering–were available to US companies (and perhaps due to penicillin and the discovery of antibiotics). By the late 1950s Mexico had 90% of the market. In the 50s, seven companies participated in the business but by the mid-60s, all were owned by global companies. By 1954, Syntex was the leader with 3000 employees including 150 chemists. In 1951, Mexico raised taxes on competitors and export permits became difficult for others. In 1956, the Senate held hearings accusing Syntex SA of misuse of patent rights owned by the US government and engaging in a cartel. In 1956, Syntex was acquired by American interests. Its headquarters and research soon moved to Palo Alto, CA. In the 1970s Mexicans became aware that barbasco was a source of valuable steroids for hormones. During the Mexican Miracle (1940-68) population had increased from 48.3mm to 70mm and many moved to Mexico City. The peso was allowed to float and quickly fell from 12.5 pesos/dollar to 25 pesos. Mexicans also noted their medications were imported. Of the 75 firms that made medications in Mexico, 30 had been acquired by foreign firms. By the mid-50s, the middle class was doing well in Mexico. Rural areas lacked newspapers, roads, telephones, and radios. In the 50s, Mexico barbasco supplied 80 to 90% of world demand; by the 70s that decreased to 40 to 45%. From 1963 to 68, world demand doubled, but Mexican output increased by one third. From 1968 to 73, demand grew by 50% but Mexican supply increased by 10%. The barbasco supply began to fade as land was converted to agriculture and ranching. Other sources evolved when Percy Julian at Glidden learned to make prednisone from soybean steroids. Luis Echeverria Alverez was elected President and set about change. In September, 1974, he ruled that yams and steroids were property of the state. Proquivemex was created in the belief Mexico could make its own pharmaceuticals. The new agency set about taking over collection of barbarosa giving responsibility to campesinos. They displaced the middlemen who had been community leaders often providing loans in family emergencies. Proquivemex attempted to increase campesinos income by raising prices but drug companies canceled orders. They had a year’s supply in inventory. Ultimately Proquivemex proved unprofitable and was shut down. The campesinos were often illiterate and lacked the necessary skills. Technology changed reducing the quantities needed for birth control pills. And diosgenin became available from Guatemala and China. A chapter describes the evolution of the economy in Mexico. The Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) was a significant event resulting in increased recognition of the rights of peasants and land reform. Echeverria’s populist government tried to use the steroid business to benefit peasants. They benefitted from the economic activity but the government program got over extended and failed. This is a detailed telling of the story of hormones from Mexican yams. Readers learn much about life in rural Mexico and efforts to make improvements. We also learn of the international cartels that traditionally have controlled the hormone business. Photos. References. Index.

| Best Sellers Rank | #444,906 in Books ( See Top 100 in Books ) #263 in Mexico History #368 in History of Medicine (Books) #743 in Pharmacology (Books) |

| Customer Reviews | 4.0 4.0 out of 5 stars (21) |

| Dimensions | 6.13 x 0.87 x 9.25 inches |

| Edition | Illustrated |

| ISBN-10 | 0822346052 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0822346050 |

| Item Weight | 1.1 pounds |

| Language | English |

| Print length | 352 pages |

| Publication date | December 23, 2009 |

| Publisher | Duke University Press |

P**H

A masterful work by an established scholar

Professor Soto-Laveaga successfully marries studies that, at first glance, appear to have little to do with each other. Yet, she convinces us that the means by which Mexican peasants hunted, processed, and sold tubers was not only scientific, but integral to the development of economically viable synthetic hormones. She raises important questions. Who produces knowledge? Where does science come from? How do human beings experience science differently? Further, she does all of this within a compelling global history of a commodity. Not to mention that I got a crash course in the history of this region. Sure, there are some portions that are stronger than others and minor imperfections here and there, but overall this is a must read for those interested in science, medicine, and globalization.

P**R

The story of hormones from Mexican yams.

“Jungle Laboratories: Mexican Peasants, National Projects, and the Making of the Pill,” by Gabriel Soto Laveaga, Duke University Press, Durham, NC, 2009. This 332-page paperback tells the story of the Mexican yams that made possible the birth control pill. In 1942, chemist Russell Marker of Penn State University found a wild yam in Mexico with a natural steroid suitable for conversion to hormones. This discovery is the basis of Syntex. Steroids are a family of chemicals with four condensed rings. Best known is cholesterol, but the family includes both male and female sex hormones as well as cortisone. Traditionally they were extracted from butchered animals but processing made them expensive. Yams changed all of that making steroidal hormones inexpensive and readily available. The book focuses on the peasants (campesinos) who collected the yams in a poor region of Southern Mexico. The yams were a source of income although middlemen often got most of the proceeds. The peasants were told the yams were used to make Fab detergent. Skilled pickers learned which were most valuable. Cultivation of the yams was attempted in Guatemala and Puerto Rico but yields were unsatisfactory. Russell Marker developed processes for the yams. He helped found Syntex in Mexico in 1944. He left when partners didn’t share profits. Carl Djerassi was a key player in the development of the pill at Syntex in California. Margaret Sanger was a major factor in the quest for the birth control pill. She was assisted by Gregory Pincus who did fundamental research. At the height of the barbasco trade ten tons of wild yams were removed from Oaxaca, Veracruz, Tabasco, and Chiapas states in Mexico per week by more than 100,000 pickers. Collectors received 10 to 60 Mexican centavos (less than a nickel) per kilogram. Campesinos wrote the President requesting roads, school houses, and electricity. Middlemen were central figures. They loaned tools to pickers in return for yams. The yams grew in dense jungle. Barbasco harvested in Veracruz was fermented, dried, bundled and shipped to Syntex in Mexico City. Other regions supplied German, Dutch and American companies. In 1941, cortisone proved effective in treating rheumatoid arthritis. Daily injections gave near complete remission. A mad scramble followed–almost as big as penicillin–to find a better source. In 1951, methods were developed to make cortisone from barbasco. In Mexico, Syntex got there first, but Upjohn soon found a fermentation process that converted progesterone from Syntex. In 1951, Upjohn ordered 10 tons of progesterone from Syntex. Global drug companies soon had subsidiaries in Mexico. Marker was born in Hagerstown, MD and studied chemistry at University of Maryland. He began the study of steroids at Rockefeller Institute but left in 1934 over a dispute on his search for plant sources of natural steroids. He moved to Penn State University where he worked on steroids under a grant from Park, Davis & Company. He published 147 papers on sterols and 75 patents (assigned to Park, Davis) between 1935 and 1943. The study of sex hormones began in the 1920s. In the 1930s, European pharmaceutical companies ran a cartel based on patents and cross-licensing agreements. Sex hormones were synthesized from cholesterol from the spinal cords of cattle or isolated from the urine of mammals, especially pregnant mares. Hormones for treatment of menopause was an early use. In 1942, Marker brought the first yams to Park, Davis, but they declined participation. He then approached other companies, but without success. He returned to Mexico on his own and took yam extract back to the US where a friend let him use his lab for one third of the progesterone produced. They made 3 kg valued at $240K. Next he partnered with Laboratorios Hormona SA in Mexico City to found Syntex in 1944. He had no capital but offered know how in return for 40% of profits. The price of progesterone fell to less then $1/gram. He left the company less than one year later. He did not reveal his process. Next he founded another company, Botanica-Mex SA. It was one of six companies producing hormones in Mexico. Marker left the company in 1949. He left chemistry and took up training silversmiths. To replace Marker, Syntex hired George Rosenkranz, a Hungarian born chemist who had settled in Cuba. To develop the chemical industry in Mexico he started a PhD program at National Autonomous University (UNAM) and lobbied for financial support at Instituto de Quimica. Instituto continues as the flagship of research in Mexico. A key player at Syntex was Luis Ernesto Miramontes. He made the first sample of norethindrone, which proved suitable for oral contraceptives. He attended UNAM. Carl Djerassi hired him at Syntex. Mexican peasants had known barbasco for its medicinal properties. If slices were thrown into water fish would come to the surface gasping for air. Healers used it as an abortifacient. A glass of tea was sufficient but could kill the mother as well as the fetus. Until World War II, European companies had dominated the pharmaceutical business. That changed after the war when patents from German companies–especially Schering–were available to US companies (and perhaps due to penicillin and the discovery of antibiotics). By the late 1950s Mexico had 90% of the market. In the 50s, seven companies participated in the business but by the mid-60s, all were owned by global companies. By 1954, Syntex was the leader with 3000 employees including 150 chemists. In 1951, Mexico raised taxes on competitors and export permits became difficult for others. In 1956, the Senate held hearings accusing Syntex SA of misuse of patent rights owned by the US government and engaging in a cartel. In 1956, Syntex was acquired by American interests. Its headquarters and research soon moved to Palo Alto, CA. In the 1970s Mexicans became aware that barbasco was a source of valuable steroids for hormones. During the Mexican Miracle (1940-68) population had increased from 48.3mm to 70mm and many moved to Mexico City. The peso was allowed to float and quickly fell from 12.5 pesos/dollar to 25 pesos. Mexicans also noted their medications were imported. Of the 75 firms that made medications in Mexico, 30 had been acquired by foreign firms. By the mid-50s, the middle class was doing well in Mexico. Rural areas lacked newspapers, roads, telephones, and radios. In the 50s, Mexico barbasco supplied 80 to 90% of world demand; by the 70s that decreased to 40 to 45%. From 1963 to 68, world demand doubled, but Mexican output increased by one third. From 1968 to 73, demand grew by 50% but Mexican supply increased by 10%. The barbasco supply began to fade as land was converted to agriculture and ranching. Other sources evolved when Percy Julian at Glidden learned to make prednisone from soybean steroids. Luis Echeverria Alverez was elected President and set about change. In September, 1974, he ruled that yams and steroids were property of the state. Proquivemex was created in the belief Mexico could make its own pharmaceuticals. The new agency set about taking over collection of barbarosa giving responsibility to campesinos. They displaced the middlemen who had been community leaders often providing loans in family emergencies. Proquivemex attempted to increase campesinos income by raising prices but drug companies canceled orders. They had a year’s supply in inventory. Ultimately Proquivemex proved unprofitable and was shut down. The campesinos were often illiterate and lacked the necessary skills. Technology changed reducing the quantities needed for birth control pills. And diosgenin became available from Guatemala and China. A chapter describes the evolution of the economy in Mexico. The Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) was a significant event resulting in increased recognition of the rights of peasants and land reform. Echeverria’s populist government tried to use the steroid business to benefit peasants. They benefitted from the economic activity but the government program got over extended and failed. This is a detailed telling of the story of hormones from Mexican yams. Readers learn much about life in rural Mexico and efforts to make improvements. We also learn of the international cartels that traditionally have controlled the hormone business. Photos. References. Index.

D**R

Excellent

Excellent and prompt; as described.

U**T

delivered on time and in good condition

I appreciate that I received my item in a timely manner despite the holiday shipping rush. The book had a nice note inside wishing me happy holidays and I would like to do the same to the seller! Thank you for the book!

M**E

First half / Second half

I used it in a class on commodities. Students liked the first 5 chapters and not the last 4. I think the story is unique compared to other standards on things like sugar or tobacco. I think the reviewer (anahuac) that points out that this is a great story but needed some editing for clarity (and I would add brevity) is on the money. The reviewer (vergara) that loved the book so much (also a UC San Diego grad - like the author ...) is right on the money about the research.

S**I

Five Stars

Quick delivery and exactly what I needed.

A**V

a fantastic book!

Jungle Laboratories is an engaging and fascinating study of a non-traditional commodity, barbasco. Clearly written and carefully researched, this book shows us the multiple ways in which transnational pharmaceutical companies' demand eventually transformed living and working conditions in the Mexican countryside. The book provides a unique window into the history of post-revolutionary Mexico, and it is a very accessible reading not only for students and academics but also for people interested in the historical interplay of science, states, and local communities. My students and I have always enjoyed reading and discussing Jungle Laboratories, and I highly recommend it.

A**E

A Perfectly Functional Book

The author takes an interesting topic, blends it with prose as dry as the Atacama, mixes it about with some poor organization and we have a fairly functional and standard academic history. A glaring example of the weak writing meeting the organizational problems is that the book relies on sub-headings for sections that are at times one paragraph long. Really? No editor at Duke could say "try using some transitions" instead of tossing in sub-heads like they were sprinkles on sundae. But again, the thesis, the evidence, and the importance of the argument are really very interesting, and I would have loved to have seen this in the hands of a far better writer. Students I read this with universally liked the topic but disliked the writing. Too bad.

A**A

Es un libro básico para entender la historia de la ciencia desde la perspectiva transnacional. La historia de la píldora anticonceptiva traza relaciones entre farmaceúticas transnacionale, campesinos y autoridades mexicanas.

C**E

Llegó súper dañado (manchado y hasta un poco húmedo). No lo pude devolver por la premura del tiempo y sus opciones de reposición.

Trustpilot

3 weeks ago

1 month ago