Some deliveries may take a little longer than usual due to regional shipping conditions.

Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

Early Summer / What Did the Lady Forget? 1951

H**R

A historic treasure

A family drama with no particular plot centered on an extended family living in Kamakura outside of Tokyo. The men are at their offensive worst ("You! My tea!" to a wife or work subordinate), the wives hold down the fort and serve their husbands meals, ready their baths, greet them off or welcome them home, and the boys are extreme brats. People are never still; they're always on the move, greeting, talking, jesting and laughing. They seem to spare no expense on meals and entertainment. The viewer can feel the energy that ran throughout post-war Japan, and since the boys would be in their late 70s in 2018, the generations of people depicted in this film are mostly the ones who would go on to shape modern-day Japan. Ozu's ending smashes the image of the extended family living under one roof, upon which the entire movie was based, and seems to warn of a future Japan comprised primarily of condo-dwelling nuclear families. A visual historic treasure of family and work life in Japan in the early 1950s. SPOILERMy favorite scene was when Aya was explaining how she had thought Noriko would end up, that is, living a privileged life nearby with a house like this and a garden like that and how, when Aya would visit, she would come out and say, "Hello, how are you?" She actually says this in beautiful English, and as a Japanese, it makes me think how its modern citizens may have retrogressed from these earlier, booming, closer-knit times.

A**N

This is my favourite movie by the director

This is my favourite movie by the director. Please use the correct movie jacket. The current image is actually Tokyo Story.

A**R

This is a well done film. Really enjoyed it.

Just a wonderful movie about Japanese family with comedic moments. Feels much more contemporary than the 1950's.

G**N

A Classic Movie - one of the top 100 to me

As another reviewer stated, this movie is as good as Tokyo Story and Late Spring. It is really a fantastic movie that is in my own top 100 of all time. It is hard to believe how good Ozu is at directing and watching Setsuko Hara acting is sublime.

A**R

quiet and beautiful.

pensive, quiet and beautiful.

D**D

A classic

My 2005 review, from my web site:In this Japanese film from 1951, 28-year-old Noriko (played by Setsuko Hara, who also appeared in Ozu’s Tokyo Story) lives with her three-generation family. She helps support them with the wages she earns in her downtown Tokyo clerical office job. Her family decides that she is getting along in years and needs to get married. The wheels of an arranged marriage start turning. This leads to complications.That’s the story. Director Ozu elevates it to high art through a combination of nuance, subtlety, beautiful acting, and masterful camera work and editing.This is a movie about a Japanese family, but the realities of family life, aging, youth, and the bittersweet nature of life all are combined into a level of truth and universality that is very rare in any cinema. This film tugs at your heart in a way that is real, not mawkish or melodramatic. The routines of daily life, however Japanese, are instantly recognizable, from the children resisting washing their faces before dinner, to the elders escaping from the home when children descend on it for an afternoon party.The phrase that come to mind when I think about the overall style and look of this film is “simply elegant.” There is nothing shiny or artificial here; everything rings true. Yet it is all so familiar that we can almost imagine that, were the dice thrown a different way and another family chosen by Ozu for exploration of a common situations, we would see a different story told with the same elegant subtlety, the same care and attention to detail, the same recognizable reality.Setsuko Hara is radiant in this film. She plays a giving, loving, and devoted character, but she does not overplay. Noriko is so self-effacing at times that you want to grab her by the shoulders, shake her, and yell, “Stop sacrificing yourself! Do what’s best for you!”

F**F

A mature masterwork and a forgotten comic gem

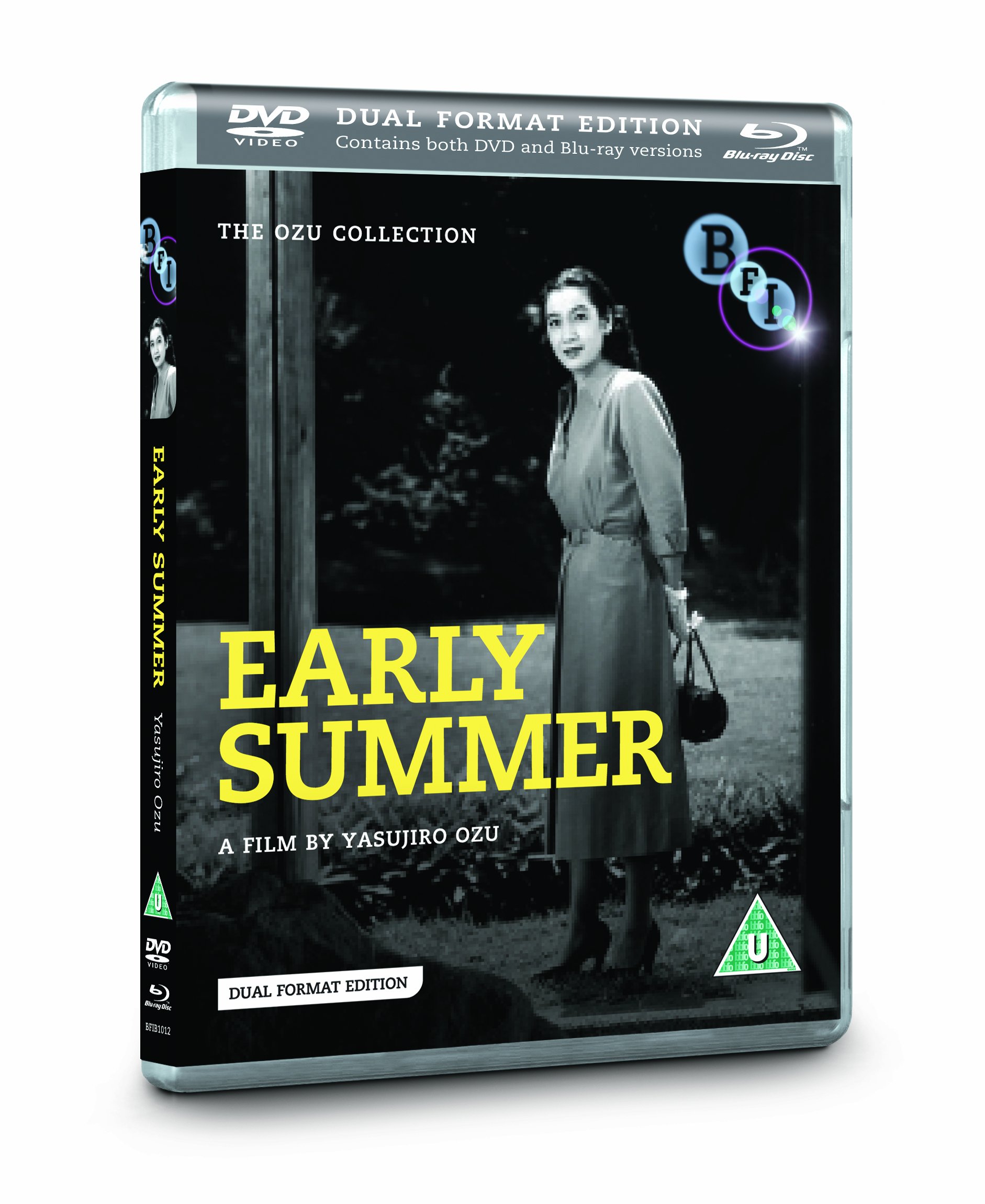

Ozu Yasujirō was one of the greatest film directors and after decades of obscurity outside Japan it is cause for celebration that at last BFI are doing him proud by releasing all 36 of his surviving films on both DVD and Blu-ray. The way the films are being released is also to be applauded. The earliest films have been offered in box sets, the Student Comedies and the Gangster Films making up two desirable items, while the late post-war masterpieces are offered in duel releases, the Blu-ray versions as supplements to the DVDs containing one `main' feature each coupled with one of his earlier sound films from the 30s/40s. In this way we get to see rare films which we ordinarily might pass over and realize that they are every bit as good as the main features they support.Ozu's greatness is evidenced by a staggeringly high level of consistency throughout his output from his early silents to his final austere masterworks. The main dish here is the wonderful Early Summer. Though overlooked by the reputations of Late Spring and Tokyo Story (the other two parts of the loose `Noriko Trilogy' which feature Hara Setsuko playing unconnected characters who share the same name) the film is possibly the most ambitious of the three and is fully their equal in terms of artistic achievement. BFI have provided a beautiful transfer here with images and sound ideally sharp. The region 1 Criterion version comes from the same source and has a Donald Richie audio commentary which must be worth hearing. However, if you go for it you will miss the precious rarity provided here by BFI - What Did the Lady Forget? This is a bubbly social satire in the manner of Ernst Lubitsch and shines fascinating light on a period of Ozu's career not well known to many. The transfer is surprisingly good with only slight deterioration in the picture quality noticeable on reel changes. I should emphasize that the Blu-ray disc only includes Early Summer. Not having a Blu-ray player I can't comment on it, but the DVD which contains both features is certainly very good. BFI have released the 2 discs with a small booklet carrying a brief article by Michael Atkinson, a remembrance of Ozu penned by Ryū Chishū, full cast details and a brief biography of Ozu by Tony Rayns. It's nice to have `something' extra on the films, but BFI really must try to keep pace with Criterion. The American company offers in addition to the Richie commentary, a conversation about Ozu between sound technician Suematsu Kojiro, cameraman Kawamata Takashi and producer Yamanouchi Shizuo. Then there's a booklet that contains essays by David Bordwell and Jim Jarmusch. I must stress though that What Did the Lady Forget? is well worth having and doesn't appear to be available elsewhere, making this BFI issue an essential purchase.Before I turn to the films in more detail, as a long-term resident in Japan I'd like to offer a few insights into what makes Ozu special. He has been called `the most Japanese' of the great directors and of the `big three' I'd say this is true though Mizoguchi Kenji also has a strong claim. But where Mizoguchi's focus lies on `high' Japanese culture (folk tales, Kabuki theater, Nōh drama, etc) Ozu's subject is everyday family life. His films reflect culture and attitudes that are unique to Japan which foreigners (I'm thinking of myself when I first arrived here 20 years ago) find opaque and difficult to comprehend. There is no doubt that the family is the central unit of Japanese society and Ozu's films are full of the feeling of maintaining `wa' (harmony) between family members and friends. Society here is anything but straightforward. Nothing is said or done directly. For example, in the Japanese language there are no words for `yes' or `no' and opinion-giving is frowned upon for fear of causing offence. It is the upholding of an agreeable `tatamae' (surface) which is the oil of Japanese social discourse. For this reason Ozu's films are full of (seemingly) mundane conversations about everyday things - the weather, basic greetings, conversation about superficial subjects and statements of the obvious. Family occasions and ceremonies assume central importance with funerals, weddings and commemoration rituals taking up so much of the narrative focus even if (through typical Ozu narrative ellipsis) they might not be shown.Japanese people generally avoid direct statement of emotions and foreigners not used to the country might find this odd and cold, but beneath the (for foreigners) bland surface harmony there is an ocean of deep emotion which is evidenced only obliquely, subtly and with great restraint. It is this feeling that lies at the heart of Ozu's universe. For those with the equipment to register it (Japanese people and those foreigners who understand their mentality) his films are extraordinarily moving. For those without, even if the technical achievements can still be grasped, the films may appear to be about nothing at all. This is the barrier preventing many from appreciating Ozu.International producers were scared to release films which seemed only to appeal to insular Japanese tastes. In the 1950s when both Ozu and Mizoguchi were arguably at their height it was perhaps their misfortune to fall under the shadow of Kurosawa Akira, their younger `rival' who propelled Japanese cinema onto the world stage in 1950 by triumphing at Cannes with Rashomon. This was the first Japanese film most Americans and Europeans had ever seen and audiences of the time can be forgiven for assuming that Kurosawa's cinema was emblematic of Japanese culture as a whole, but looked at objectively we can see that influences on Kurosawa (ranging from Shakespeare to Dostoyevsky and from John Ford to Carl Theodor Dreyer) were fundamentally western. In fact his films have never sat easily with some Japanese people because of their bold metaphysical speculation where images and script are always aiming to `make a statement'. It's important to realize that this is fundamentally a western aesthetic and that a number of people in Japan accused Kurosawa (some still do) of intellectual snobbery and arrogance. The fact that after he left Toho studio in 1965 he had difficulty finding funds, ending up going to Russia to make Dersu Uzala and then making Kagemusha, Dreams and Ran with foreign money, shows how much he was ill-trusted in his home country.Contrast Kurosawa with Ozu. Ozu was a life-long Shochiku company `salaryman', making only 3 of his 53 films away from that studio. From the time of The Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family onwards he was considered a model of reliability in that he made shomingeki (domestic dramas) which made pots of money for Shochiku who were happy to let him use their best actors and technicians. Foreigners might see Ozu as an art house name, a director who made odd films of little interest to a wider audience. Actually, he was hugely popular in Japan, capturing great commercial success when he was alive. The artists that made up the Ozu family who always worked with him (writers Fushimi Akira, Ikeda Tadao and Noda Kōgo; cameramen Yuharu Atsuta and Mohara Hideo; composers Itō Senji and Saitō Kojun; actors Hara Setsuko, Iida Choko, Mitsui Koji, Miyake Kuniko, Sugimura Haruko, Ryū Chishū, Saburi Shin and others) all owe their careers to him and stay deeply loved by Japanese people to this day. Unlike Mizoguchi, Ozu showed indifference to whether he was accepted (or even distributed) overseas and was content to make films about his favorite subjects, adopting reactionary techniques which seemed to contradict the norm at the time, but consequently now seem so modern with his achievements surely set to last. Ozu's famous `minimalist' technique is rendered through his suppression of usual dramatic effect by the heavy usage of narrative ellipse, a camera that almost never moves, cutaway so-called `pillow shots' of buildings or nature which act as continuity links, precise `square' framing of images with a low camera looking up at characters (an aesthetic reflecting the interior design of Japanese houses and the screens and tatami straw mats which surround lives which take place mainly on the floor), and a tendency to shoot actors' faces full-on rather than using the over-the-shoulder, action-reaction approach of traditional Hollywood cinema. This puts the audience squarely in the film itself, a feeling alien to those weaned on the western norm.The world of Ozu isn't so different from the world of his Japanese audiences when his films were first released and the attendant themes involved (family conflict, social transition, a search for selflessness which is seldom found, the growing up process) reverberate strongly even in today's society in Japan. His films are simple, dedicated and reflect on the deepest of emotions in everyday life without resorting to intellectual bombast or camera trickery. Ozu's aesthetic is pure, subtle, refined and it is in this indirect appeal to our emotions that he shows his innate Japanese-ness. I have already said that Japanese people are not known for showing their emotions directly, but that does not mean they are not emotional. An Ozu film is a hugely emotional experience which is achieved as it were out of nothing. The biggest compliment you can give an actor, a writer or a director is where the mechanics of their craft disappear, and in an Ozu film everything seems effortless and completely natural. One would never know Ozu had prepared each scene meticulously at the script stage, had every camera set-up firmly in his head in advance and went on to demand absolute obedience to his complex preparations from everyone while shooting on set.In the 50s when Europe was about to be hit by a French New Wave of vibrant self-reflexive film-making, the reactionary Ozu was going in the opposite direction, crafting out exquisite family dramas where ticks and tropes of style don't exist. We are moved in a profound and quietly devastating manner which is really quite unique to him, though echoes of his style are to be found today in the films of Hou Hsiao Hsien and Kore-eda Hirokazu. In fact in a world where the films of Theo Angelopoulos, Abbas Kiarostami and Béla Tarr (other masters of the narrative ellipse who are often accused of obscurity) have found sympathetic audiences around the world perhaps the climate is now right for Ozu to be recognized everywhere as the master he really was.WHAT DID THE LADY FORGET? (Shukujo wa nani o wasureta ka)(Japan, 1937, 71 minutes, b/w, Japanese language - English subtitles, Original aspect ratio 1.33:1)Ozu's second talkie, this film was the comic rebound Shochiku studio wanted after the gloomy and hopeless masterpiece The Only Son. Anyone coming to it from late Ozu will be surprised at the light breezy touch evidenced here, but those familiar with his early silent student comedies will know what to expect. Ozu (under his usual pen-name `James Maki') wrote the script together with Fushimi Akira. They had collaborated on the earlier silent I Was Born, But...(1932) and much of the same humor flows through the film though the social milieu has changed from the working class shitamachi (lower-town) setting of that film to an upper-middle class central Tokyo setting demarcated by the circular Yamanote train line. At its most serious the film is a social satire on the way stuffy old fashioned tradition must give way (is giving way?) to the new represented primarily by the release of a young woman's power and the effect it has on the older generation. The story concerns the effect spoiled modern woman Setsuko (Kuwano Kayoko) has on the married life of her uncle, Dr. Komiya (Saito Tatsuo) and his overbearing wife, Tokiko (Kurishima Sumiko) when she comes from Osaka to stay with them. It would spoil your enjoyment if I gave the plot away so I will resist the temptation to write a closer analysis. Suffice it to say, Ozu gives us a number of delightful situations which really work - the gaggle of women (including Iida Choko unrecognizable from her role as the tragic mother in The Only Son) gossiping together at the beginning and then later at a kabuki theater, the student falling asleep in Komiya's university class, the boys (including Tokkan Kozō familiar from numerous other Ozu features) dissing their private teacher, Okada (Sano Shuji), Komiya being taken to a Geisha establishment by his wicked niece, his pretense to reprimand her in front of his irate wife, and the wonderful comic denouement which ends in a very un-pc slap for the culprit deserving of it. Everyone gets their come-uppance and learns a thing or two in Ozu's light frothy treatment. The end result is rather like Lubitsch meets Hawks relocated to Japan in screwball-mode. Ozu's mise-en-scène is the usual static kind with tremendous movement in and out of frame, but the camera does move at least 6 times (probably more than in all his last 13 films put together!) in the film's duration and there is a Hawaiian hula soundtrack which you'd never ordinarily associate with this director. All in all the film is a delightful surprise and hopefully will inspire people to investigate his equally funny earlier student comedies.EARLY SUMMER (Bakushū)(Japan, 1951, 125 minutes, b/w, Japanese language - English subtitles, Original aspect ratio 1.33:1)Ozu's 44th film is the centerpiece of the `Noriko Trilogy' and at first glance would appear to carry on the same concerns of the preceding Late Spring. Again the film features Hara Setsuko as a not-so-young single lady named Noriko who is heading to be `Christmas cake' (the unkind Japanese term for ladies who have just past the age of 25 - their sell-by date on the marriage market). Again the poor girl has to put up with family pressure to marry quickly. Then there is the disintegration of the family which is the result of children marrying off coupled with the social transition of younger ideas encroaching in on old fashioned tradition. On one level this is a completely natural thing, but as with all Ozu films of this period it is something heightened by Japan's defeat in World War II and a change which has been imposed suddenly and un-naturally from outside (the American occupation). Ozu was never specific about this (he usually avoided any political commentary and wasn't allowed to in any case), but it undoubtedly gives a somber feel to events as they transpire.However, despite obvious parallels Early Summer is very different from Late Spring. Where the earlier film concerns itself very tightly with the father-daughter relationship, Early Summer is arguably much more ambitious in approaching similar material through the viewpoints of at least ten different characters in and around the family. Three generations live under one roof in the Mamiya household in Kamakura, the Tokyo suburb familiar from Late Spring. The first 30 minutes of the film casually (but precisely) introduces the family to us. To the chimes of the popular melody "There's No Place Like Home" we meet the grandparents, Shukichi (Sugai Ichiro) and Shige (Higashiyama Chieko), their children Noriko and her older brother Koichi (Ryū Chishū), Koichi's wife Fumiko (Miyake Kuniko) and their two children. Then there is the neighbor Yabe Tami (Sugimura Haruko) whose son Kenkichi (Hiroshi Nihonyanagi) was the best friend of Noriko and Koichi's younger brother Shoji who is still MIA six years after the end of the war. Ozu delightfully charts the everyday life of these people with his customary emphasis on manners and observance of other people's feelings. Only the grandchildren are allowed a quotient of freedom and they are indulged by everyone throughout. The acting is very natural and I can't think of another instance from an Ozu film which so perfectly captures the Japanese spirit of `wa' in family life as here.The story proper kicks in when Shukichi's older brother (Kodo Kokuten) visits and suggests it's time Noriko gets married. Much of the film's central section is devoted to Noriko, her job as a secretary in Tokyo working for Satake Sotaro (Sano Shuji), and to her friends who are a mixture of wives and singletons. Her relationship with her friend Tamura Aya (Awashima Chikage) perhaps tells us the most about her real feelings which turn out to be ones of independence and self-assertion very different from the Noriko character of Late Spring. In a way typical of many families in Japan, the Mamiyas get very excited when a colleague of Noriko's boss puts down a marriage proposal to Noriko from his friend Manabe. The man is rich and has good family connections. Omiai (arranged marriage) is often viewed in Japan as a way to ensure a woman's future security and for Koichi (the most practical in the family) the fact that the man is 42 doesn't matter. Both Shige and Fumiko register regret at the age disparity, but this is nothing compared to their reaction to the news that Noriko decides to ignore Manabe and suddenly accepts a proposal from their neighbor Kenkichi who himself doesn't know anything about the match until his mother informs him of the news. One of the funniest moments of the films comes after his mother and Noriko have just agreed to the proposal when Noriko walks past her future husband on the street exchanging a simple greeting, the son not knowing that he is about to get hitched to this woman.Western audiences will always view omiai with a degree of suspicion, but the situation as portrayed here is very typical of this culture. Some western commentators have concluded that the film shows the family is saddened because they think Noriko makes a bad choice. It's true the man is a widower, has a young child and is not especially rich, but it's not correct to say they think it's a bad match. Kenkichi is roughly Noriko's age and has been known to the Mamiya family for a very long time - something that makes him perhaps a better choice than the much older stranger Manabe. The family is saddened not by the choice, but by the fact that she makes the choice on her own without talking to anyone about it. Noriko's sudden impulse flies in the face of proper Japanese etiquette where big decisions are decided by family discussion and agreement based on mutual consent. The family expresses their anger mainly through Koichi who reprimands her for not thinking about them. Her mother Shige even says, "I feel like I don't know my daughter any more". This anger is based on the family's concern (and is actually an expression of their love) for Noriko who is making a life-changing decision not only for herself, but also for everyone else in the family whose lives will not be the same without her. Western commentators will take the side of Noriko and insist she has the right to do what she wants and the family has no right to make her sad about the decision she has made, but as the film demonstrates the decision Noriko makes does break up the family. She moves to Akita (in northern Japan) to be with her husband in his new job, the grandparents move to the country to live with the uncle who visited earlier, and Koichi and his family are left alone to live in Kamakura.Ozu's point in Early Summer is that we might try to hold on to happiness in the perfect bliss of the situation charted at the beginning, but life is a state of perpetual flux. Like it or not, things can never be the same forever. At different points each character in Ozu's masterly tapestry of family life state their sadness at the impermanence of things and the transient nature of happiness. This is summed up perfectly when old man Shukichi takes a walk to the train tracks, sits down and waits at the crossing for the train to pass. He has said earlier in the film that now the family is at their happiest, but the train (as always with Ozu) is the perfect symbol for the certainty of change. The only certainty of life is life's uncertainty. This film broods on this fact to heart-breaking effect - the old couple watching a balloon flying away in the sky leaving some child unhappy somewhere, Koichi's stunned reaction to the impending loss of his sister, Fumiko's realization on the sand dune that Noriko's departure will leave a gaping hole in the fabric of her family's everyday life, and Noriko's own realization that her actions will have such a profound effect upon those who love her.Early Summer's central theme of the transience of all things is echoed strongly in the original Japanese title of the film, Bakushū meaning "The Barley Harvest Season". One of the things that draws Noriko to Kenkichi is the fact that the man was her late brother Shoji's best friend. In a restaurant scene he reveals that he has kept a letter from Shoji in which is enclosed an ear of barley. This links in with the film's wondrous final shots of the barley fields around the house where old Shukichi and Shige end up living. They watch a bridal procession cross the fields as the camera (unusually mobile for Ozu) tracks and then fades into darkness. The central idea here is the concept of `rinne', the transmigration of the soul. Shoji is probably dead and is reincarnated as an ear of barley so that by connection all the ears of barley in the fields at the film's close are the souls of Japan's war dead. The wedding procession (and of course Noriko's union with Kenkichi) is a subtle statement that despite the carnage of war life must go on. As Ozu said about the film, "I wanted to describe such deep matters as reincarnation and mutability, more than just telling a story".Ozu's mise-en-scène in Early Summer is absolutely staggering throughout. I recommend David Bordwell's book on Ozu which gives an analysis of the film virtually shot by shot. Framed with images of the transience of life and death (the opening sea waves and the closing barley fields) the film showcases Ozu's trademark static style. Ozu repeatedly cuts back to the same shots to remarkable effect - the bird cage hanging from the ceiling, the shot of the kitchen down the corridor, the main living area with kotatsu (low heated table which is the center of family meals and important conversations) and screens framing characters with a low camera as they flit in and out in the happy hubbub of daily life, the alley outside the house down which characters return from work. Then there are the Ozu-trademark `pillow shots'. My favorite is the shot of koinobori (kites shaped as carp) fluttering in the breeze after the grandparents have been talking about Shoji, their son who is probably dead. Koinobori are flown every May (late spring / early summer!) to celebrate the birth and healthy growth of all boys in Japan. The effect of loss for the old couple here is deeply moving. But what astonishes even more in the film is the subtle profundity of the way Atsuta Yuharu and Ozu move their camera. I've already mentioned the final tracking shot and fade (both unusual for this director), but throughout there are tiny movements which throw off and underline bigger meanings and emotions. The camera follows the boys down the road by the sea empathizing with their loneliness. Then the camera follows Noriko and Aya down a corridor towards a room where we are promised a glimpse of the mysterious potential suitor Manabe. The camera backs away as the ladies advance towards it only for Ozu to reverse the angle completely to give us a shot of the now familiar interior of the Mamiya home. This is a typical example of Ozu ellipsis which in addition to playing a joke on us also makes clear that Manabe is really not that important to Noriko or her family after all. His existence is irrelevant to Ozu's central subject and is therefore elided.Where Late Spring and Tokyo Story center on character conflicts (the father and daughter in the first, the old couple and their uncaring offspring in the second) and are therefore melodramatic to a degree, Early Summer centers on a whole family (representing the whole of Japanese society perhaps) which despite the best intentions of all concerned, can't help but change naturally within itself. As such, melodrama is largely eschewed and therein lays the genius of this film. Everything about it is natural and unforced. Ozu observes with warm wisdom, absolutely refusing to judge any of his characters and making magic out of mundane everyday life. Never has social transition embedded within daily routine seemed so remarkable.

F**F

A mature masterwork and a forgotten comic gem

Ozu Yasujirō was one of the greatest film directors and after decades of obscurity outside Japan it is cause for celebration that at last BFI are doing him proud by releasing all 36 of his surviving films on both DVD and Blu-ray. The way the films are being released is also to be applauded. The earliest films have been offered in box sets, the Student Comedies and the Gangster Films making up two desirable items, while the late post-war masterpieces are offered in duel releases, the Blu-ray versions as supplements to the DVDs containing one `main' feature each coupled with one of his earlier sound films from the 30s/40s. In this way we get to see rare films which we ordinarily might pass over and realize that they are every bit as good as the main features they support.Ozu's greatness is evidenced by a staggeringly high level of consistency throughout his output from his early silents to his final austere masterworks. The main dish here is the wonderful Early Summer. Though overlooked by the reputations of Late Spring and Tokyo Story (the other two parts of the loose `Noriko Trilogy' which feature Hara Setsuko playing unconnected characters who share the same name) the film is possibly the most ambitious of the three and is fully their equal in terms of artistic achievement. BFI have provided a beautiful transfer here with images and sound ideally sharp. The region 1 Criterion version comes from the same source and has a Donald Richie audio commentary which must be worth hearing. However, if you go for it you will miss the precious rarity provided here by BFI - What Did the Lady Forget? This is a bubbly social satire in the manner of Ernst Lubitsch and shines fascinating light on a period of Ozu's career not well known to many. The transfer is surprisingly good with only slight deterioration in the picture quality noticeable on reel changes. I should emphasize that the Blu-ray disc only includes Early Summer. Not having a Blu-ray player I can't comment on it, but the DVD which contains both features is certainly very good. BFI have released the 2 discs with a small booklet carrying a brief article by Michael Atkinson, a remembrance of Ozu penned by Ryū Chishū, full cast details and a brief biography of Ozu by Tony Rayns. It's nice to have `something' extra on the films, but BFI really must try to keep pace with Criterion. The American company offers in addition to the Richie commentary, a conversation about Ozu between sound technician Suematsu Kojiro, cameraman Kawamata Takashi and producer Yamanouchi Shizuo. Then there's a booklet that contains essays by David Bordwell and Jim Jarmusch. I must stress though that What Did the Lady Forget? is well worth having and doesn't appear to be available elsewhere, making this BFI issue an essential purchase.Before I turn to the films in more detail, as a long-term resident in Japan I'd like to offer a few insights into what makes Ozu special. He has been called `the most Japanese' of the great directors and of the `big three' I'd say this is true though Mizoguchi Kenji also has a strong claim. But where Mizoguchi's focus lies on `high' Japanese culture (folk tales, Kabuki theater, Nōh drama, etc) Ozu's subject is everyday family life. His films reflect culture and attitudes that are unique to Japan which foreigners (I'm thinking of myself when I first arrived here 20 years ago) find opaque and difficult to comprehend. There is no doubt that the family is the central unit of Japanese society and Ozu's films are full of the feeling of maintaining `wa' (harmony) between family members and friends. Society here is anything but straightforward. Nothing is said or done directly. For example, in the Japanese language there are no words for `yes' or `no' and opinion-giving is frowned upon for fear of causing offence. It is the upholding of an agreeable `tatamae' (surface) which is the oil of Japanese social discourse. For this reason Ozu's films are full of (seemingly) mundane conversations about everyday things - the weather, basic greetings, conversation about superficial subjects and statements of the obvious. Family occasions and ceremonies assume central importance with funerals, weddings and commemoration rituals taking up so much of the narrative focus even if (through typical Ozu narrative ellipsis) they might not be shown.Japanese people generally avoid direct statement of emotions and foreigners not used to the country might find this odd and cold, but beneath the (for foreigners) bland surface harmony there is an ocean of deep emotion which is evidenced only obliquely, subtly and with great restraint. It is this feeling that lies at the heart of Ozu's universe. For those with the equipment to register it (Japanese people and those foreigners who understand their mentality) his films are extraordinarily moving. For those without, even if the technical achievements can still be grasped, the films may appear to be about nothing at all. This is the barrier preventing many from appreciating Ozu.International producers were scared to release films which seemed only to appeal to insular Japanese tastes. In the 1950s when both Ozu and Mizoguchi were arguably at their height it was perhaps their misfortune to fall under the shadow of Kurosawa Akira, their younger `rival' who propelled Japanese cinema onto the world stage in 1950 by triumphing at Cannes with Rashomon. This was the first Japanese film most Americans and Europeans had ever seen and audiences of the time can be forgiven for assuming that Kurosawa's cinema was emblematic of Japanese culture as a whole, but looked at objectively we can see that influences on Kurosawa (ranging from Shakespeare to Dostoyevsky and from John Ford to Carl Theodor Dreyer) were fundamentally western. In fact his films have never sat easily with some Japanese people because of their bold metaphysical speculation where images and script are always aiming to `make a statement'. It's important to realize that this is fundamentally a western aesthetic and that a number of people in Japan accused Kurosawa (some still do) of intellectual snobbery and arrogance. The fact that after he left Toho studio in 1965 he had difficulty finding funds, ending up going to Russia to make Dersu Uzala and then making Kagemusha, Dreams and Ran with foreign money, shows how much he was ill-trusted in his home country.Contrast Kurosawa with Ozu. Ozu was a life-long Shochiku company `salaryman', making only 3 of his 53 films away from that studio. From the time of The Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family onwards he was considered a model of reliability in that he made shomingeki (domestic dramas) which made pots of money for Shochiku who were happy to let him use their best actors and technicians. Foreigners might see Ozu as an art house name, a director who made odd films of little interest to a wider audience. Actually, he was hugely popular in Japan, capturing great commercial success when he was alive. The artists that made up the Ozu family who always worked with him (writers Fushimi Akira, Ikeda Tadao and Noda Kōgo; cameramen Yuharu Atsuta and Mohara Hideo; composers Itō Senji and Saitō Kojun; actors Hara Setsuko, Iida Choko, Mitsui Koji, Miyake Kuniko, Sugimura Haruko, Ryū Chishū, Saburi Shin and others) all owe their careers to him and stay deeply loved by Japanese people to this day. Unlike Mizoguchi, Ozu showed indifference to whether he was accepted (or even distributed) overseas and was content to make films about his favorite subjects, adopting reactionary techniques which seemed to contradict the norm at the time, but consequently now seem so modern with his achievements surely set to last. Ozu's famous `minimalist' technique is rendered through his suppression of usual dramatic effect by the heavy usage of narrative ellipse, a camera that almost never moves, cutaway so-called `pillow shots' of buildings or nature which act as continuity links, precise `square' framing of images with a low camera looking up at characters (an aesthetic reflecting the interior design of Japanese houses and the screens and tatami straw mats which surround lives which take place mainly on the floor), and a tendency to shoot actors' faces full-on rather than using the over-the-shoulder, action-reaction approach of traditional Hollywood cinema. This puts the audience squarely in the film itself, a feeling alien to those weaned on the western norm.The world of Ozu isn't so different from the world of his Japanese audiences when his films were first released and the attendant themes involved (family conflict, social transition, a search for selflessness which is seldom found, the growing up process) reverberate strongly even in today's society in Japan. His films are simple, dedicated and reflect on the deepest of emotions in everyday life without resorting to intellectual bombast or camera trickery. Ozu's aesthetic is pure, subtle, refined and it is in this indirect appeal to our emotions that he shows his innate Japanese-ness. I have already said that Japanese people are not known for showing their emotions directly, but that does not mean they are not emotional. An Ozu film is a hugely emotional experience which is achieved as it were out of nothing. The biggest compliment you can give an actor, a writer or a director is where the mechanics of their craft disappear, and in an Ozu film everything seems effortless and completely natural. One would never know Ozu had prepared each scene meticulously at the script stage, had every camera set-up firmly in his head in advance and went on to demand absolute obedience to his complex preparations from everyone while shooting on set.In the 50s when Europe was about to be hit by a French New Wave of vibrant self-reflexive film-making, the reactionary Ozu was going in the opposite direction, crafting out exquisite family dramas where ticks and tropes of style don't exist. We are moved in a profound and quietly devastating manner which is really quite unique to him, though echoes of his style are to be found today in the films of Hou Hsiao Hsien and Kore-eda Hirokazu. In fact in a world where the films of Theo Angelopoulos, Abbas Kiarostami and Béla Tarr (other masters of the narrative ellipse who are often accused of obscurity) have found sympathetic audiences around the world perhaps the climate is now right for Ozu to be recognized everywhere as the master he really was.WHAT DID THE LADY FORGET? (Shukujo wa nani o wasureta ka)(Japan, 1937, 71 minutes, b/w, Japanese language - English subtitles, Original aspect ratio 1.33:1)Ozu's second talkie, this film was the comic rebound Shochiku studio wanted after the gloomy and hopeless masterpiece The Only Son. Anyone coming to it from late Ozu will be surprised at the light breezy touch evidenced here, but those familiar with his early silent student comedies will know what to expect. Ozu (under his usual pen-name `James Maki') wrote the script together with Fushimi Akira. They had collaborated on the earlier silent I Was Born, But...(1932) and much of the same humor flows through the film though the social milieu has changed from the working class shitamachi (lower-town) setting of that film to an upper-middle class central Tokyo setting demarcated by the circular Yamanote train line. At its most serious the film is a social satire on the way stuffy old fashioned tradition must give way (is giving way?) to the new represented primarily by the release of a young woman's power and the effect it has on the older generation. The story concerns the effect spoiled modern woman Setsuko (Kuwano Kayoko) has on the married life of her uncle, Dr. Komiya (Saito Tatsuo) and his overbearing wife, Tokiko (Kurishima Sumiko) when she comes from Osaka to stay with them. It would spoil your enjoyment if I gave the plot away so I will resist the temptation to write a closer analysis. Suffice it to say, Ozu gives us a number of delightful situations which really work - the gaggle of women (including Iida Choko unrecognizable from her role as the tragic mother in The Only Son) gossiping together at the beginning and then later at a kabuki theater, the student falling asleep in Komiya's university class, the boys (including Tokkan Kozō familiar from numerous other Ozu features) dissing their private teacher, Okada (Sano Shuji), Komiya being taken to a Geisha establishment by his wicked niece, his pretense to reprimand her in front of his irate wife, and the wonderful comic denouement which ends in a very un-pc slap for the culprit deserving of it. Everyone gets their come-uppance and learns a thing or two in Ozu's light frothy treatment. The end result is rather like Lubitsch meets Hawks relocated to Japan in screwball-mode. Ozu's mise-en-scène is the usual static kind with tremendous movement in and out of frame, but the camera does move at least 6 times (probably more than in all his last 13 films put together!) in the film's duration and there is a Hawaiian hula soundtrack which you'd never ordinarily associate with this director. All in all the film is a delightful surprise and hopefully will inspire people to investigate his equally funny earlier student comedies.EARLY SUMMER (Bakushū)(Japan, 1951, 125 minutes, b/w, Japanese language - English subtitles, Original aspect ratio 1.33:1)Ozu's 44th film is the centerpiece of the `Noriko Trilogy' and at first glance would appear to carry on the same concerns of the preceding Late Spring. Again the film features Hara Setsuko as a not-so-young single lady named Noriko who is heading to be `Christmas cake' (the unkind Japanese term for ladies who have just past the age of 25 - their sell-by date on the marriage market). Again the poor girl has to put up with family pressure to marry quickly. Then there is the disintegration of the family which is the result of children marrying off coupled with the social transition of younger ideas encroaching in on old fashioned tradition. On one level this is a completely natural thing, but as with all Ozu films of this period it is something heightened by Japan's defeat in World War II and a change which has been imposed suddenly and un-naturally from outside (the American occupation). Ozu was never specific about this (he usually avoided any political commentary and wasn't allowed to in any case), but it undoubtedly gives a somber feel to events as they transpire.However, despite obvious parallels Early Summer is very different from Late Spring. Where the earlier film concerns itself very tightly with the father-daughter relationship, Early Summer is arguably much more ambitious in approaching similar material through the viewpoints of at least ten different characters in and around the family. Three generations live under one roof in the Mamiya household in Kamakura, the Tokyo suburb familiar from Late Spring. The first 30 minutes of the film casually (but precisely) introduces the family to us. To the chimes of the popular melody "There's No Place Like Home" we meet the grandparents, Shukichi (Sugai Ichiro) and Shige (Higashiyama Chieko), their children Noriko and her older brother Koichi (Ryū Chishū), Koichi's wife Fumiko (Miyake Kuniko) and their two children. Then there is the neighbor Yabe Tami (Sugimura Haruko) whose son Kenkichi (Hiroshi Nihonyanagi) was the best friend of Noriko and Koichi's younger brother Shoji who is still MIA six years after the end of the war. Ozu delightfully charts the everyday life of these people with his customary emphasis on manners and observance of other people's feelings. Only the grandchildren are allowed a quotient of freedom and they are indulged by everyone throughout. The acting is very natural and I can't think of another instance from an Ozu film which so perfectly captures the Japanese spirit of `wa' in family life as here.The story proper kicks in when Shukichi's older brother (Kodo Kokuten) visits and suggests it's time Noriko gets married. Much of the film's central section is devoted to Noriko, her job as a secretary in Tokyo working for Satake Sotaro (Sano Shuji), and to her friends who are a mixture of wives and singletons. Her relationship with her friend Tamura Aya (Awashima Chikage) perhaps tells us the most about her real feelings which turn out to be ones of independence and self-assertion very different from the Noriko character of Late Spring. In a way typical of many families in Japan, the Mamiyas get very excited when a colleague of Noriko's boss puts down a marriage proposal to Noriko from his friend Manabe. The man is rich and has good family connections. Omiai (arranged marriage) is often viewed in Japan as a way to ensure a woman's future security and for Koichi (the most practical in the family) the fact that the man is 42 doesn't matter. Both Shige and Fumiko register regret at the age disparity, but this is nothing compared to their reaction to the news that Noriko decides to ignore Manabe and suddenly accepts a proposal from their neighbor Kenkichi who himself doesn't know anything about the match until his mother informs him of the news. One of the funniest moments of the films comes after his mother and Noriko have just agreed to the proposal when Noriko walks past her future husband on the street exchanging a simple greeting, the son not knowing that he is about to get hitched to this woman.Western audiences will always view omiai with a degree of suspicion, but the situation as portrayed here is very typical of this culture. Some western commentators have concluded that the film shows the family is saddened because they think Noriko makes a bad choice. It's true the man is a widower, has a young child and is not especially rich, but it's not correct to say they think it's a bad match. Kenkichi is roughly Noriko's age and has been known to the Mamiya family for a very long time - something that makes him perhaps a better choice than the much older stranger Manabe. The family is saddened not by the choice, but by the fact that she makes the choice on her own without talking to anyone about it. Noriko's sudden impulse flies in the face of proper Japanese etiquette where big decisions are decided by family discussion and agreement based on mutual consent. The family expresses their anger mainly through Koichi who reprimands her for not thinking about them. Her mother Shige even says, "I feel like I don't know my daughter any more". This anger is based on the family's concern (and is actually an expression of their love) for Noriko who is making a life-changing decision not only for herself, but also for everyone else in the family whose lives will not be the same without her. Western commentators will take the side of Noriko and insist she has the right to do what she wants and the family has no right to make her sad about the decision she has made, but as the film demonstrates the decision Noriko makes does break up the family. She moves to Akita (in northern Japan) to be with her husband in his new job, the grandparents move to the country to live with the uncle who visited earlier, and Koichi and his family are left alone to live in Kamakura.Ozu's point in Early Summer is that we might try to hold on to happiness in the perfect bliss of the situation charted at the beginning, but life is a state of perpetual flux. Like it or not, things can never be the same forever. At different points each character in Ozu's masterly tapestry of family life state their sadness at the impermanence of things and the transient nature of happiness. This is summed up perfectly when old man Shukichi takes a walk to the train tracks, sits down and waits at the crossing for the train to pass. He has said earlier in the film that now the family is at their happiest, but the train (as always with Ozu) is the perfect symbol for the certainty of change. The only certainty of life is life's uncertainty. This film broods on this fact to heart-breaking effect - the old couple watching a balloon flying away in the sky leaving some child unhappy somewhere, Koichi's stunned reaction to the impending loss of his sister, Fumiko's realization on the sand dune that Noriko's departure will leave a gaping hole in the fabric of her family's everyday life, and Noriko's own realization that her actions will have such a profound effect upon those who love her.Early Summer's central theme of the transience of all things is echoed strongly in the original Japanese title of the film, Bakushū meaning "The Barley Harvest Season". One of the things that draws Noriko to Kenkichi is the fact that the man was her late brother Shoji's best friend. In a restaurant scene he reveals that he has kept a letter from Shoji in which is enclosed an ear of barley. This links in with the film's wondrous final shots of the barley fields around the house where old Shukichi and Shige end up living. They watch a bridal procession cross the fields as the camera (unusually mobile for Ozu) tracks and then fades into darkness. The central idea here is the concept of `rinne', the transmigration of the soul. Shoji is probably dead and is reincarnated as an ear of barley so that by connection all the ears of barley in the fields at the film's close are the souls of Japan's war dead. The wedding procession (and of course Noriko's union with Kenkichi) is a subtle statement that despite the carnage of war life must go on. As Ozu said about the film, "I wanted to describe such deep matters as reincarnation and mutability, more than just telling a story".Ozu's mise-en-scène in Early Summer is absolutely staggering throughout. I recommend David Bordwell's book on Ozu which gives an analysis of the film virtually shot by shot. Framed with images of the transience of life and death (the opening sea waves and the closing barley fields) the film showcases Ozu's trademark static style. Ozu repeatedly cuts back to the same shots to remarkable effect - the bird cage hanging from the ceiling, the shot of the kitchen down the corridor, the main living area with kotatsu (low heated table which is the center of family meals and important conversations) and screens framing characters with a low camera as they flit in and out in the happy hubbub of daily life, the alley outside the house down which characters return from work. Then there are the Ozu-trademark `pillow shots'. My favorite is the shot of koinobori (kites shaped as carp) fluttering in the breeze after the grandparents have been talking about Shoji, their son who is probably dead. Koinobori are flown every May (late spring / early summer!) to celebrate the birth and healthy growth of all boys in Japan. The effect of loss for the old couple here is deeply moving. But what astonishes even more in the film is the subtle profundity of the way Atsuta Yuharu and Ozu move their camera. I've already mentioned the final tracking shot and fade (both unusual for this director), but throughout there are tiny movements which throw off and underline bigger meanings and emotions. The camera follows the boys down the road by the sea empathizing with their loneliness. Then the camera follows Noriko and Aya down a corridor towards a room where we are promised a glimpse of the mysterious potential suitor Manabe. The camera backs away as the ladies advance towards it only for Ozu to reverse the angle completely to give us a shot of the now familiar interior of the Mamiya home. This is a typical example of Ozu ellipsis which in addition to playing a joke on us also makes clear that Manabe is really not that important to Noriko or her family after all. His existence is irrelevant to Ozu's central subject and is therefore elided.Where Late Spring and Tokyo Story center on character conflicts (the father and daughter in the first, the old couple and their uncaring offspring in the second) and are therefore melodramatic to a degree, Early Summer centers on a whole family (representing the whole of Japanese society perhaps) which despite the best intentions of all concerned, can't help but change naturally within itself. As such, melodrama is largely eschewed and therein lays the genius of this film. Everything about it is natural and unforced. Ozu observes with warm wisdom, absolutely refusing to judge any of his characters and making magic out of mundane everyday life. Never has social transition embedded within daily routine seemed so remarkable.

T**S

Two fine films

"Early Summer" (1951), in 4:3 aspect ratio, is standard Ozu fare : that is to say, it is simply very good, looking at the subtleties of Japanese family life as it is influenced by changing times. This is one of his first post- WW2 films on this theme, the recurrent one in so many of his films both before and after the war. It is to be enjoyed at leisure, and it will leave one with that bitter-sweet feeling that the nothing stays the same, but there is nought to be gained by regretting in vain such inevitability."What Did The Lady Forget" (1937) is more of a melodrama, yet it too deals with the old and the new : here, it is the rebellious, headstrong young woman, at odds with her conservatively authoritarian aunt, and encouraging her uncle to assert himself against her - all portrayed with typical Ozu restraint and gentility.

L**U

A lovely little film from Ozu, examining his usual ...

A lovely little film from Ozu, examining his usual territory of family relationships. Not as mind-blowing as Last Spring or Tokyo Story, but still worth watching, particularly for the luminous Setsuko Hara.

B**S

Recommend...

Wonderful.

フ**ト

「麦秋」と「淑女は何を忘れたか」を収録

2010年英国のBFIからのリリース。小津監督作品の2枚組。DISK1はリージョンBのBDで「麦秋」(1951年)を、DISK2はリージョン・フリーのDVDで、「麦秋」(1951年)と「淑女は何を忘れたか」(1937年)をそれぞれ収録しています。「麦秋」は十年以上前にレンタル・コピーしたDVDと比較したところ、白黒のコントラストの鮮やかさや、キレのある画面等かなりの高画質と感じました。それと個人的には「晩春」、本作そして「東京物語」の所謂「紀子三部作」の中で、原節子が最も美しいのは本作と、今回の鑑賞で改めて確信いたしました。中でも作品後半、近所に住む幼馴染の二本柳寛の母親の杉村春子を訪ねた時に、二本柳が留守でいないのにもかかわらず杉村に対し、息子との結婚を承諾してしまうという、あまりにも有名なシーンでの原の美しさは、まさしく筆舌に尽くしがたい。さらにそれを聞いて嬉しさのあまり、原に対して思わず「アンパン食べる?」と口走ってしまう杉村のお芝居も最高ですね。「麦秋」に関してはDISK2のDVD版も画質に大差なく、安心して鑑賞できます。「淑女は何を忘れたか」の方は2003年の小津生誕100周年に松竹がリリースしたDVDと比較しましたが、画質は大差なく、ややボンヤリした感じの画面のままです。ただし、音声は本ディスクの方がかなり明瞭になっていると感じました。こちらは夭折の名女優、桑野通子(1915~1946)の溌剌とした美しさと、戦前戦中の小津作品常連であった斎藤達雄の、おとぼけ芝居のコントラストが際立った傑作コメディです。2019年2月現在の本ディスクの最低価格は千円台。その値段で購入できるのであれば、「麦秋」がメイン・ターゲットで「淑女」はおまけでも、十分にCP高い優良ディスクと太鼓判です。

Trustpilot

2 weeks ago

3 weeks ago