Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

Full description not available

E**K

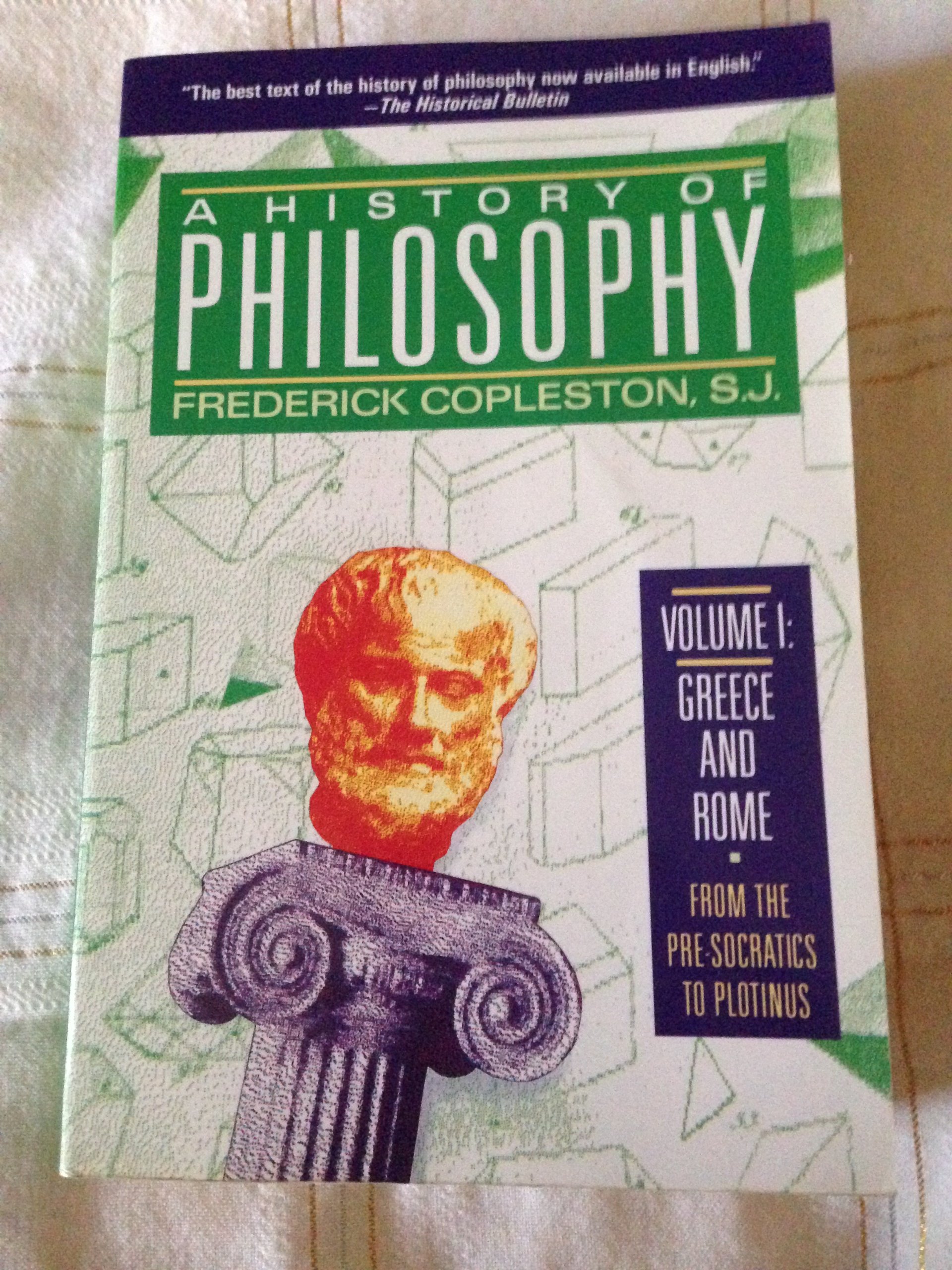

Detailed, Informative & A Pleasure to Read!

This is a great book! It covers most of the early Greek and Roman philosophers in considerably more detail in one volume than other books do. The author provides an informed, honest and unbiased (in my opinion) summary of each philosopher that includes fragments of the philosopher's own works as well as constructive arguments for and against the theories. There is A LOT of detail in this volume! Plato and Aristotle do get much larger sections than other philosophers, but arguably that is right as their contribution to western philosophy was proportionally much more extensive (though not necessarily more significant) than their predecessors. I don't think you could find a better summary of philosophical viewpoints during this time period combined with concise (but detailed) analysis of the respective theories in light of the views of the philosopher's contemporaries as well as more contemporary viewpoints.The author's goal was to create an objective study guide for Catholic seminary students whose philosophical lessons and history were sparse and very surface level. He succeeded at much more than that! This book is wonderful, the writing style is engaging and the philosophies are presented in a relevant and understandable manner. I highly recommend this book to anyone interested in improving their knowledge of western philosophy and their own lives.I have a Degree in Philosophy (sp. Ancient Phl. & Epistemology), I read this book every few years and am always amazed at the immensity of what I missed the last few times I read it. A couple other supplementary texts that you can look into are: "A Presocratics Reader" ed. by Patricia Curd and "The Presocratic Philosophers" by Kirk/Raven/Schofield. These have translations of many of the fragments available from the original philosophers that Copeland writes about. Another book is the two volumes by Diogenes Laertius, who considered himself the biographer of the early philosophers and helped preserve much biographical information about them. The last mentioned is less philosophical on the whole.Also check out all the other volumes in Copeland's History of Philosophy series, they are all equally well composed and exceptionally detailed. I wish I had known about them while I was getting my degrees!

I**L

Philosophy - the basics

The volume is "the first volume of a complete history of philosophy". (p.v) Although to "mention a "point of view" at all, when treating of the history of philosophy, may occasion a certain lifting of eyebrows" (p. v), the author has "no hesitation in claiming the right to compose a work on the history of philosophy from the standpoint of the Scholastic philosopher"(p. vi) as "no true historian can write without some point of view, some standpoint, if for no other reason than that he must have a principle of selection, guiding his intelligent choice and arrangement of facts." (p. v) Scholastic philosophers study philosophy as the "philosophia perennis". (p. 2)Modern philosophers, especially since René Descartes (A.D. 1596 - A.D. 1650) and Immanuel Kant (A.D. 1724- A.D. 1804), divorce thought from reality and start like Descartes from Consciousness, from the fact that man has innate ideas in his mind.This is not the starting-point of Copleston and others who study philosophy as the perennial philosophy. They start from Being, not from Consciousness, and for them it is reality which imposes its structures on the mind, not like Kant, the mind imposing its structures on reality.This perennial philosophy has been outlined by Plato (428 B.C. - 348 B.C.) and Aristotle (384 B.C. - 322 B.C.) and elaborated by St. Thomas Aquinas (c. A.D. 1225 - A.D. 1274). For Copleston, perennial philosophy is Thomism in a wide sense. The Thomist system is however not closed at any given historical epoch and incapable of further development in any direction. (p. 7)Most intellectuals today, on the one hand, view Plato as interested in ideas and Aristotle as interested in things and they maintain, on the other hand, that Plato separated the Form from the objects of which it is the Form, whereas Aristotle argued that to the universal in the mind, there corresponds the specific essence in the object.Plato's and Aristotle's philosophies are therefore diametrically opposed, they say, some even going so far as to label Plato as a neo-Kantian. Copleston demonstrates that Plato is not a neo-Kantian. Copleston concludes that Platonism and Aristotelianism "should not be considered as two diametrically opposed systems, but as two complementary philosophical spirits and bodies of doctrine." (Volume I, p. 275) After having argued that a synthesis between the Platonic Theory of Forms and the Aristotelian view of the universal was needed (Volume I, p. 203), Copleston will demonstrate in Volume II how St. Thomas Aquinas achieved this synthesis and harmonised the synthesis with Christian theology. This is why, as mentioned earlier, for Copleston, perennial philosophy is Thomism in a wide sense. This also explains why for Copleston, the first three volumes of his History - Greece and Rome, Medieval Philosophy, and, Late Medieval and Renaissance Philosophy - form only one volume, why Volume III ends with "A Brief Review of the First Three Volumes" and why this review cannot but contain references to Volumes II and III.A quick review of the history of Western thought will suffice to bear out the constant presence of Plato's and Aristotle's philosophies. In philosophy and in everyday life, the questions "What do you mean?" and "How do you know?" will be constantly present. It was therefore important to demonstrate that there is no contradiction between the Platonic and Aristotelian bases of the principles we need to answer these questions, Aristotle's principle of non-contradiction saying that the same attribute cannot at the same time belong and not belong to the same subject and in the same respect. This is Copleston's achievement in the present Volume I, which therefore also contains its own "Concluding Review".Copleston will conclude the final volume of his History, Volume XI, by saying that, for him, the problem of God is THE metaphysical problem par excellence. One can criticise this conclusion but one should also recognise that the argument is consistent with one of the conclusions of the present Volume I wherein Copleston argues that Greek philosophy was a preparatory intellectual instrument for Christianity, a "preparatio evangelica." (Volume I, p.502).In his own critique of the present Volume I, Copleston writes on p. 408 of Volume III of the History that he does "not think ... that one is justified in interpreting the pre-Socratics as nothing more than speculative forerunners of science." (Volume III, p. 408)Many readers complain about the quotations in languages other than English. Those readers seem to forget that the book is not "An Introduction to Philosophy" but "A History of Philosophy". They also seem to forget that in the present Internet age, search engines and translation programs are available at no cost. When looking up the translation, you learn a lot. As Copleston puts it: "Mental effort and perseverance are no doubt required in order to penetrate the riches of Greek thought, but any effort that is expended in the attempt to understand and appreciate the philosophy of these two men of genius, Plato and Aristotle, is amply rewarded." (Volume I, p. 486)

A**N

The Best History of Philosophy in English, in a Subpar Edition

Fr. Copleston set out, with this series, to provide Catholic seminarians with a solid understanding of the history of philosophy, and of those philosophies which have been or are important. He succeeds in this spectacularly, but it must be noted that Fr. Copleston's intended audience is an educated one who already has a firm grasp of basic philosophical concepts. This book is not for people completely new to the study of philosophy. It is written densely and throws a lot of information and terminology at you. That said, if you do have a command of the basics and a high reading level, there is no better source for a general history of philosophy (certainly favor this over Bertrand Russel's far inferior A History of Western Philosophy).I am withholding the final star, though, not due to any deficit in Fr. Copleston's work, but because this edition (New York: Doubleday, 1993) is rather poor. First of all the covers of Doubleday's series are silly (though at least consistent). Worse though, the text itself is poorly set and fuzzy, letters tend to melt into each other, and especially in Volume I, which makes such heavy use of Greek, the Greek letters are often difficult to parse, if not altogether indecipherable. However the book is still largely readable, and though unfortunate, the poor quality of the typesetting should not prevent anyone from picking this up who would otherwise be interested. Just be warned, hopefully a new edition will be published sometime in the near future, and this great series will be given the run of print it deserves.

Trustpilot

2 months ago

2 weeks ago